RuneScape's Half Jug of Wine: The OG Bitcoin

This blog post explores the roles that digitally-scarce assets play in virtual economies, and how these roles help interpret the rise of Bitcoin. All opinions are my own.

Part I: My golden years of market-making

The price of Bitcoin recently moved past its 2017 high watermark of $20,000. With this resurgence comes both renewed faith and criticism for the digitally-scarce asset. To detractors, Bitcoin is a bubble: it has no inherent value beyond the price others are willing to pay for it. Therefore, it is an instrument of speculation destined to burst. Bill Gates famously called it an asset of “greater fools”.

I am far from a cryptocurrency expert, and I certainly don’t want to opine on future Bitcoin prices. But on the topic of digital scarcity, I can offer something. You see, while digital scarcity in the real world is still a relatively new concept, it has existed within video games for years. Its use cases within virtual worlds could help elucidate Bitcoin’s rise, and I had a front seat growing up.

As a 13-year-old, I played a lot of RuneScape. RuneScape was a massively multiplayer roleplaying game (MMORPG) set in a fantasy medieval world. It boasted millions of players in the early 2000s. It also had a player-driven economy, meaning the price of goods were entirely determined by players who traded with one another. In other words, it was a free market.

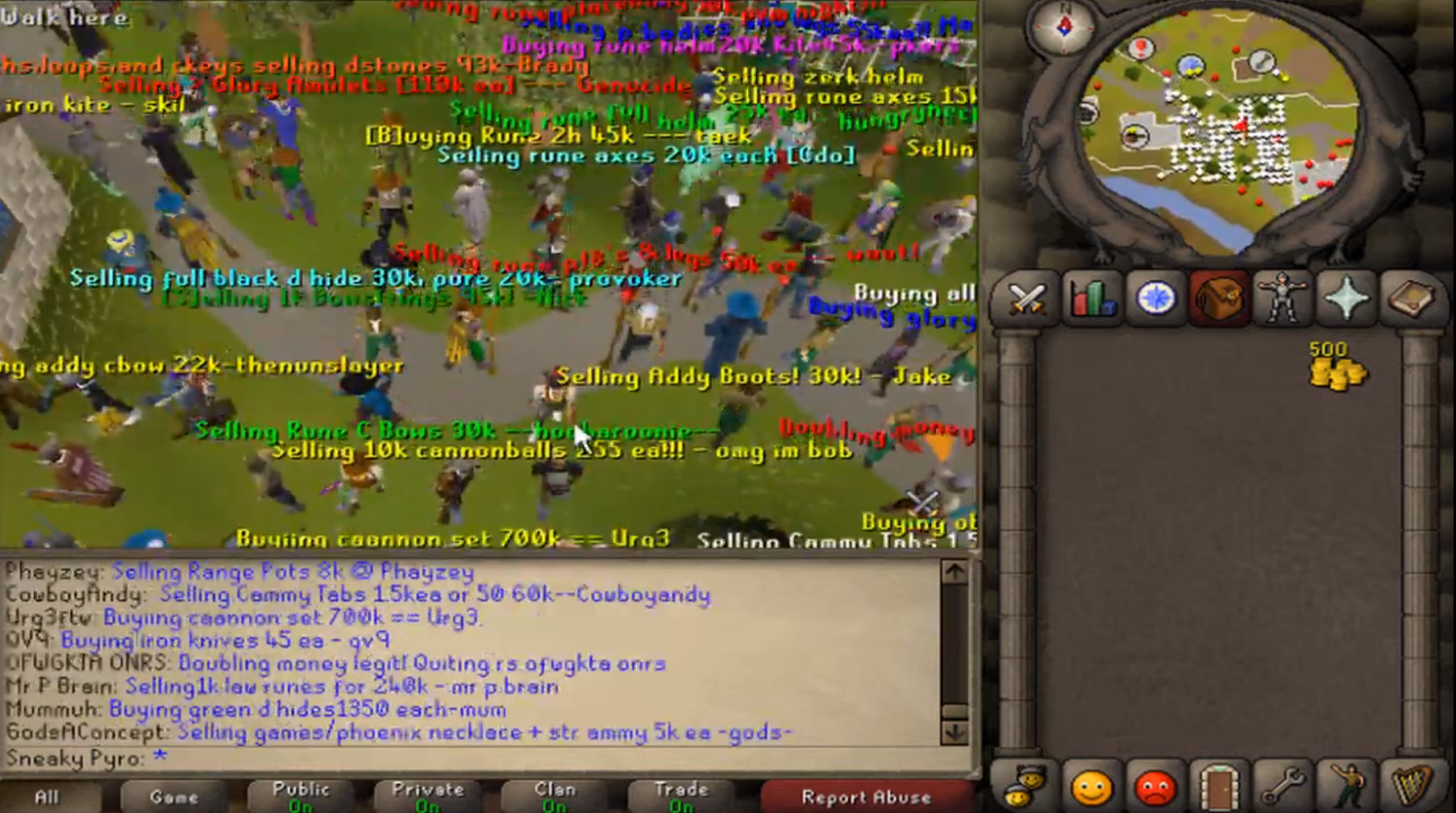

The way I played RuneScape was a bit odd. I didn’t really care for quests or dungeons or levels. I just wanted to make money. At the time, the player community had formed organic marketplaces around certain in-game locations and servers. If you needed to buy or sell something, you’d go to these spots to trade with other players.

I was a constant fixture in these markets, buying items for cheap and selling at a mark-up. I didn’t know the term at the time, but I was essentially a market-maker that moved goods between sellers and buyers. And I was great at it. I tracked prices, volumes, and spreads across vast arrays of virtual items. Perhaps it’s because of this proclivity for business that I eventually ended up at Wharton for my MBA—but that’s another story for another post.

What’s relevant here is that my role as a market-maker gave me a unique view into RuneScape’s digital economy. Here’s how it worked. Tradable goods within RuneScape were divided into three categories. The first were the consumables: arrows, potions, food, runes for magic, and so on. These goods fluctuated in price over the short term but tended to be fairly stable over the long run. If one type of arrow became too pricey, for example, less people would use it and more people would manufacture it. This was basic supply and demand.

The second type of goods were the durables: armor, weapons, and so on. They were the virtual equivalents of TVs, computers, and fridges. Players needed them, but not often. Almost uniformly, these items depreciated in price over time. Players paid princely sums for new armors when they first came out. But as more supply became available (e.g., through monster drops) and as better armor came out, prices would fall. This was not dissimilar to the price journey of consumer appliances in the real world. As market-makers, we were careful not to hold durables for too long.

Then there was the third type: the discontinued items. These were a very, very small set of items that, for one reason or another, could not be created anymore within the game, ever. In other words, they were supply-capped. One example was the Party Hat. Party Hats were ‘dropped’ by RuneScape devs in 2001 for a Christmas celebration event, when the game was still in its infancy. Some of the Party Hats survived in the game years later and became collectible items.

Beside their limited stock, the most notable quality about discontinued items was that they were uniformly useless. These items did not grant special abilities or power or benefits. Some, like the Party Hat, were at least wearable and could signal a player’s wealth (like hanging a Picasso in your mansion or wearing a gold chain, I presume). Other items could not even do that.

The ‘Half Jug of Wine’ was one such item. Early in the game’s history, wine was drunk in two gulps. A ‘Full Jug of Wine’, when drunk once, became a ‘Half Jug of Wine’. Drunk again, it became an ‘Empty Jug’. At some point, developers decided that wine should just be drunk in one gulp to make life easier. But when they implemented this change, they inadvertently created a discontinued item in ‘Half Jug of Wine’, though few who owned half-jugs realized it at the time.

For market-makers, trading in discontinued items was the holy grail. By 2004, these items had become expensive. And because many players didn’t know how to properly value them, the spread for market-makers was enormous. We scoured the player base for older players who stumbled on these items and forgot to sell. They were often the least clued-in on market prices.

Part II: The true value of the Half-Jug

Before going further, it’s helpful here to introduce RuneScape’s currency and money supply system. The virtual currency within the game was the Gold Coin (gp). Players earned gp for completing various tasks, such as killing monsters and raiding dungeons. In this sense, the money supply was dynamic: new coins were introduced to the game economy by players playing the game, and old coins were taken out of circulation as players quit.

In 2004, an iron arrow, a common consumable, cost around 10 gp. A good armor set cost around 40,000 gp. The most expensive Party Hat was around 1 million gp. This was a price well beyond the reach of new players, but motivated veterans could conceivably get there with a few weeks to months of “grind”.

Then, beginning in late 2004, RuneScape saw a large influx of new players, which meaningfully increased the game’s money supply. The effect of this increased money supply was not noticeable for the average player, for the additional money was counterbalanced by the increased volume of goods generated by the player economy. If we had constructed a hypothetical basket of in-game goods as a consumer price index (CPI), we would not have noticed much inflation.

For the discontinued goods market, it was an entirely different story. Most of the new money supply wound through the system towards the top. In these supply-capped goods, prices exploded. Party Hats went from 1 million gp in 2004 to 10 million, to over 100 million gp just a year and half later. Other discontinued items saw similar magnitudes of price increase. For the vast majority of RuneScape players, these items became solidly unobtainable.

A curious change had also taken in the mindset of market-makers like me who traded in these rare goods. We began to store, value, and denominate our net worth in discontinued items. We no longer cared about how much gold coins we owned. Cash, to misquote Ray Dalio, was trash, because it could not keep up with the inflation of these supply-capped items. Instead, we measured our success on how many more Party Hats and Half-Jug Wines we had compared to others and months before.

With hindsight, this mentality shift was profound. Discontinued items had shifted from being another type of good we traded in, to becoming our denominator of wealth. In other words, these ‘useless’ items became monetary goods and stores of value for the super rich. Put even more simply, they became proto-money for the 0.1%.

I sometimes think I understand why older generations hesitate with digitally scarce assets like Bitcoin. After all, absolute scarcity is incredibly difficult to come by in the physical world. Most things of value can be replicated and reproduced. The closest analogy would be if Picasso painted ten thousand absolutely identical versions of the same painting and then promptly dropped dead, ensuring no more could ever be made. Furthermore, these paintings had to be easily transportable and instantly verifiable. This was simply not possible in the physical world.

Yet for those of us who grew up participating in digital economies, the concept of digital scarcity comes naturally because we have already experienced them. From RuneScape, to Gaia Online, to Neopets, to World of Warcraft, the use of digitally scarce items as stores of value and monetary goods have been observed over and over again.

Take the ‘Half Jug of Wine’ as an example. Today, it is worth 1.5 billion gp in RuneScape, a number almost unfathomable to any new player. A new player might come across an ‘Empty Jug’ in his first 15 minutes of game play. He could earn enough to buy a ‘Full Jug of Wine’ in his first hour . Yet he may ‘grind’ for a decade and not be able to afford a Half Jug of Wine. We don’t need talking heads on primetime news to recognize the absurdity of it all—if we only measured the value of the Half Jug by its practical use.

But doing so would be exactly missing the point. The ‘Half Jug’ is not valued on its ability to provide practical benefit to a player, but rather on its ability to store value. It became a bubble as soon as it became more expensive than a ‘Full Jug of Wine’ sometime in the early 2000s. Yet, almost two decades later, that bubble still has not burst. Instead, the ‘Half Jug’ became a monetary good.

In 2006, RuneScape introduced the Grand Exchange, a centralized goods market. It rendered my role as market-maker obsolete. In any case, I was getting ready for high school and had drifted away from the game. As a last act, I converted my remaining in-game holdings to discontinued items—just in case.

I never tried to log back in again, except once in college, when I realized that my account and digital holdings in RuneScape had ballooned to be worth tens of thousands of dollars (that’s USD). I considered selling my account, but had forgotten my password and recovery over the years.

If I had managed to sell my account, I wonder whether I would’ve appreciated the role that digitally scarce assets played in building my virtual wealth, and whether I would’ve been astute enough to invest some of that windfall in a new digitally-scarce asset that was coming up around that time. Probably not, but you live and you learn.

Like the article? Subscribe to the mailing list to receive notifications of new blog posts